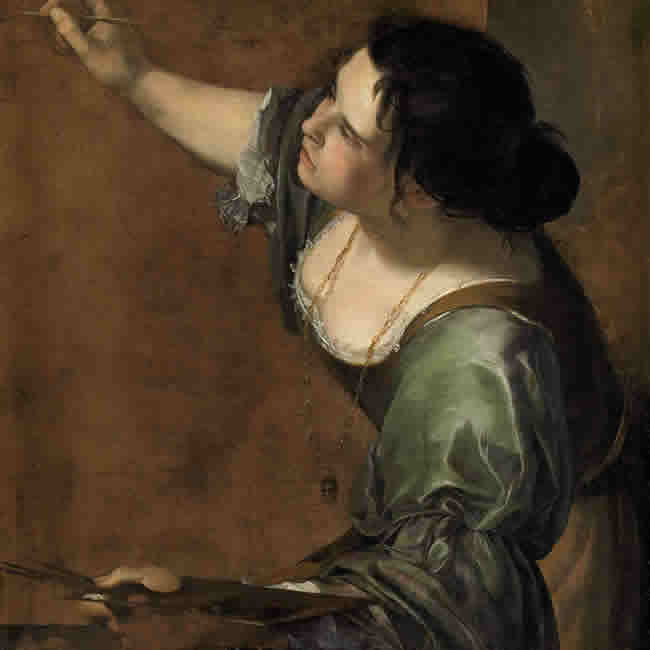

Public Domain / Google Cultural Institute

Artemisia Gentileschi (July 8, 1593–date unknown, 1653) was an Italian Baroque painter who worked in the Caravaggist style. She was the first female painter admitted to the prestigious Accademia de Arte del Disegno. Gentleschi's art is often discussed in connection to her biography: she was raped by an artist colleague of her father and she participated in the prosecution of the rapist, two facts that many critics connect with the themes of her work. Today, Gentileschi is recognized for her expressive style and the remarkable achievements of her artistic career.

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome in 1593 to Prudentia Montoni and Orazio Gentileschi, a successful painter. Her father was friends with the great Caravaggio, the father of the dramatic style that would come to be known as the Baroque.

The young Artemisia was taught to paint in her father’s studio at a young age and would eventually take up the trade, though her father insisted she join a convent after the death of her mother in childbirth. Artemisia could not be deterred, and eventually her father became a champion of her work.

Much of Gentileschi’s legacy lies in the sensationalism surrounding her rape at the hands of her father’s contemporary and her painting teacher, Agostino Tassi. After Tassi refused to marry Gentileschi, Orazio brought his daughter’s rapist to trial.

There, Gentileschi was made to repeat the details of the attack under the duress of an early "truth-telling" device called a sibille, which progressively tightened around her fingers. By the trial's end, Tassi was found guilty and sentenced to five years banishment from Rome, which he never served. Many speculate his punishment was not enforced, as he was a favorite artist of Pope Innocent X.

After the trial, Gentileschi married Pierantonio Stiattesi (a minor Florentine artist), had two daughters, and became one of the most desirable portrait painters in Italy.

Gentileschi achieved great success in her lifetime—a rare degree of success for a female artist of her era. An incontestable example of this is her admittance to the prestigious Accademia del Disegno, founded by Cosimo de Medici in 1563. As a member of the guild, Gentileschi was able to purchase paints and other art materials without the permission of her husband, which proved to be instrumental when she decided to separate herself from him.

With newfound freedom, Gentileschi spent time painting in Naples and later in London, where she was summoned to paint at the court of the King Charles I around 1639. Gentileschi was also patronized by other noblemen (among them the powerful Medici family) and members of the Church in Rome.

Artemisia Gentileschi's most famous painting is of the Biblical figure of Judith, who beheads the general Holofernes in order to save her village. This image was depicted by many artists throughout the Baroque period; typically, artists represented the character of Judith as either the temptress, who uses her wiles to lure a man who she later kills, or the noble woman, who is willing to sacrifice herself to save her people.

Gentileschi’s depiction is unusual in its insistence on Judith’s strength. The artist does not shy away from depicting her Judith as struggling to sever the head of Holofernes, which results in an image both evocative and believable.

Many scholars and critics have likened this image to a self-portrait of revenge, suggesting that the painting was Gentileschi’s way of asserting herself against her rapist. While this biographical element of the work could be true—we do not know the psychological state of the artist—the painting is equally important for the way it represents Gentileschi's talent and her influence on Baroque art.

This is not to say, however, that Gentileschi was not a strong woman. There is much evidence of her confidence in herself as a female painter. In many of her correspondences, Gentileschi referenced the difficulty of being a female painter in a male dominated field. She was vexed by the suggestion that her work might not be as good as that of her male counterparts, but never doubted her own ability. She believed her work would speak for itself, responding to one critic that her painting would show him "what a woman can do."

Gentileschi's now famous self-portrait, Self-portrait as the Allegory of Painting, was forgotten in a cellar for centuries, as it was thought to have been painted by an unknown artist. That a woman could have produced the work was not considered possible. Now that the painting has been properly attributed, it proves to be a rare example of a combination of two artistic traditions: the self portrait and the embodiment of an abstract idea by a female figure—an achievement that no male painter could create himself.

Though her work was well-received during her lifetime, Artemisia Gentileschi’s reputation floundered after her death in 1653. It is not until 1916 that interest around her work was revived by Robert Longhi, who wrote about Artemisia’s work in conjunction with her father’s. Longhi’s wife would later publish on the younger Gentileschi in 1947 in the form of a novel, which focused on the dramatic unfolding of her rape and its aftermath. The inclination to dramatize Gentileschi's life continues today, with several novels and a movie about the artist’s life.

In a more contemporary turn, Gentileschi has become a 17th century icon for a 21st century movement. The parallels of the #metoo movement and the testimony of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford in the Brett Kavanaugh hearings put Gentileschi and her trial back into the public consciousness, with many citing Gentileschi’s case as evidence that little progress has been made in the intervening centuries when it comes to public responses to female victims of sexual violence.