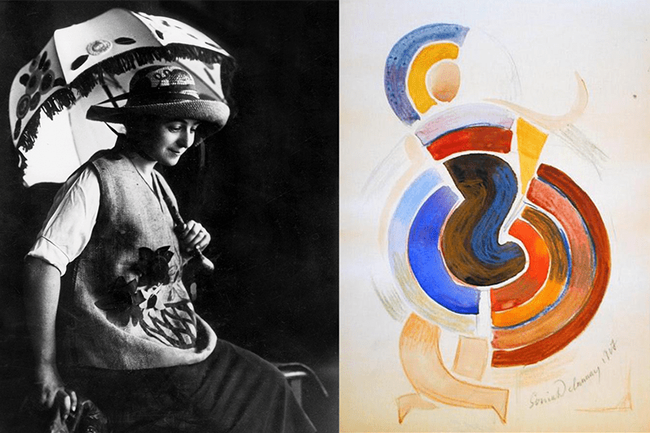

L: Apic/Hulton Archives/Getty Images. R: WikiArt/Public Domain.

Sonia Delaunay (born Sophia Stern; November 14, 1885 – December 5, 1979) was one of the pioneers of abstract art at the turn of the century. She is best known for her participation in the art movement of Simultaneity (also known as Orphism), which placed vibrant contrasting colors alongside one another in order to stimulate the feeling of movement in the eye. She was also a highly successful textile and clothing designer, making a living off of the colorful dress and fabric designs she produced in her Paris studio.

Sonia Delaunay was born Sophia Stern in 1885 in Ukraine. (Though she lived there only briefly, Delaunay would cite the brilliant sunsets of Ukraine as the inspiration behind her colorful textiles.) By the age of five she had moved to Saint Petersburg to live with her wealthy uncle. She was eventually adopted by their family and became Sonia Terk. (Delaunay is sometimes referred to as Sonia Delaunay-Terk.) In St. Petersburg, Delaunay lived the life of a cultured aristocrat, learning German, English, and French and traveling often.

Delaunay moved to Germany to attend art school, and then eventually went on to Paris, where she enrolled in l'Académie de la Palette. While in Paris, her gallerist Wilhelm Uhde agreed to marry her as a favor, so that she could avoid moving back to Russia.

Though a marriage of convenience, her association with Uhde would prove instrumental. Delaunay exhibited her art for the first time at his gallery and through him met many important figures in the Parisian art scene, including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and her future husband, Robert Delaunay. Sonia and Robert married in 1910, after Sonia and Uhde amicably divorced.

In 1911, Sonia and Robert Delaunay's son was born. As a baby blanket, Sonia sewed a patchwork quilt of brilliant colors, reminiscent of the bright colors of folkloric Ukrainian textiles. This quilt is an early example of the Delaunays’ commitment to Simultaneity, a way of combining contrasting colors to create a sensation of movement in the eye. Both Sonia and Robert used it in their painting to evoke the fast pace of the new world, and it became instrumental to the appeal of Sonia’s home furnishings and fashions which she would later turn into a commercial business.

Twice a week, in Paris, the Delaunays attended the Bal Bullier, a fashionable nightclub and ballroom. Though she would not dance, Sonia was inspired by the movement and action of dancing figures. At the turn of the century, the world was rapidly industrializing, and artists found figurative representation to be insufficient in describing the changes they were observing. For Robert and Sonia Delaunay, saturation of color was the way to depict the electric vibrations of modernity and the best way to describe the subjectivity of the self.

Advances in the science of color theory had proved that perception was inconsistent among individual perceivers. The subjectivity of color, as well the realization that vision was a state of perpetual flux, was a reflection of the unstable world of political and social change in which the only thing man could verify was his individual experience. As an expression of her subjective self, as well as due to her fascination with juxtaposing color, Sonia made the first simultaneous dresses, much like the colorful patchwork quilts she made for her son, which she wore to the Bal Bullier. Soon she was making similar items of clothing for her husband and the various poets and artists close to the couple, including a vest for poet Louis Aragon.

At the outbreak of World War I, Sonia and Robert were vacationing in Spain. They decided not to return to Paris, but instead to exile themselves to the Iberian Peninsula. They successfully settled into expat life, using the isolation to focus on their work.

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, Sonia lost the income that she had been receiving from her aunt and uncle in St. Petersburg. Left with little means while living in Madrid, Sonia was forced to found a workshop which she named Casa Sonia (and later renamed to Boutique Simultanée upon return to Paris). From Casa Sonia, she produced her increasingly popular textiles, dresses, and home goods. Through her connections with fellow Russian Sergei Diaghilev, she designed eye popping interiors for the Spanish aristocracy.

Delaunay became popular at a moment in which fashion was significantly changing for young European women. The First World War demanded that women enter the workforce, and as a result, their attire had to change to accommodate their new tasks. After the war was over, it was difficult to convince these women to return to the more restrictive dress of the 1900s and 1910s. Figures like Delaunay (and, perhaps most famously, her contemporary Coco Chanel) designed for the New Woman, who was more interested in freedom of movement and expression. In this way, Delaunay’s designs, which focused on movement of the eye across their patterned surfaces, also encouraged movement of the body in their loose fits and billowing scarves, proving two-fold that Delaunay was a champion of this radically new and exciting lifestyle. (Not to mention that she was the primary breadwinner for her family, making Sonia an exemplar for New Womanhood.)

Delaunay’s exuberance and interest in multimedia collaboration, as well as her creative and social friendships with artistic Parisian notables, were fruitful grounds for collaborations. In 1913, Delaunay illustrated the poem Prose du transsibérien, written by the couple’s good friend, Surrealist poet Blaise Cendrars. This work, now in the collection of Britain’s Tate Modern, bridges the gap between poetry and the visual arts and uses Delaunay’s understanding of undulating form to illustrate the action of the poem.

Her collaborative nature also led her to her design costumes for many stage productions, from Tristan Tzara’s play the Gas Heart to Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Delaunay’s output was defined by the fusion of creativity and production, where no element of her life was relegated to a single category. Her designs adorned the surfaces of her living space, covering the wall and furniture as wallpaper and upholstery. Even the doors in her apartment were decorated with poems scrawled by her many poet friends.

Sonia Delaunay’s contribution to French art and design was acknowledged by the French government in 1975 when she was named an officer of the Legion d’Honneur, the highest merit awarded to French civilians. She died in 1979 in Paris, thirty-eight years after her husband's death.

Her effusiveness for art and color has had lasting appeal. She continues to be celebrated posthumously in retrospectives and group shows, independently and alongside the work of her husband Robert. Her legacy in the worlds of both art and fashion will not soon be forgotten.