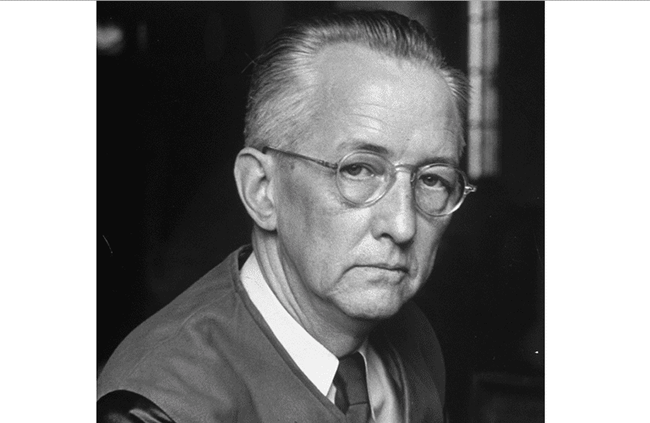

Alfred Eisenstaedt / The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images

Charles Sheeler (July 16, 1883 - May 7, 1965) was an artist who received acclaim for both his photography and painting. He was a leader of the American Precisionist movement which focused on realistic depictions of strong geometric lines and forms. He also revolutionized commercial art blurring the lines between advertising and fine art.

Born and raised in a middle-class family in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Charles Sheeler received encouragement from his parents to pursue art from an early age. After graduating from high school, he attended the Pennsylvania School of Industrial Art to study industrial drawing and applied arts. At the academy, he met American impressionist painter William Merritt Chase who became his mentor and modernist painter and photographer Morton Schamberg who became his best friend.

During the first decade of the 20th century, Sheeler traveled to Europe with his parents and Schamberg. He studied painters from the Middle Ages in Italy and visited Michael and Sarah Stein, patrons of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, in Paris. The Cubist style of the latter two had a significant impact on Sheeler's later work.

When he returned to the U.S., Sheeler knew that he could not support himself with income from his painting alone, so he turned to photography. He taught himself to take photos with a $5 Kodak Brownie camera. Sheeler opened a photography studio in Doylestown, Pennsylvania in 1910 and earned money photographing construction projects of local architects and builders. The wood stove in Sheeler's house in Doylestown, Pennsylvania was the subject of many of his early photographic works.

In the 1910s, Charles Sheeler supplemented his income by photographing works of art for both galleries and collectors. In 1913, he participated in the landmark Armory Show in New York City that exhibited the works of the most noted American modernists of the time.

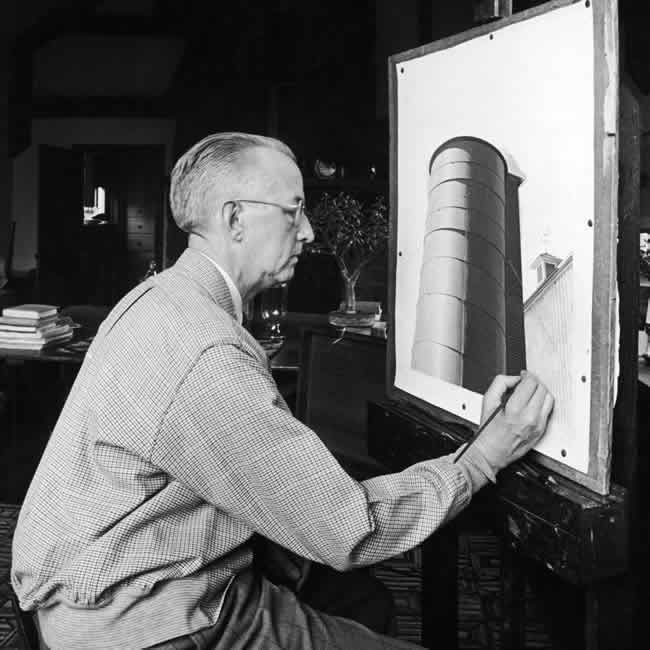

After the tragic death of his best friend Morton Schamberg in the influenza pandemic of 1918, Charles Sheeler moved to New York City. There, the streets and buildings of Manhattan became the focus of his work. He worked with fellow photographer Paul Strand on the 1921 short film Manhatta. Following its exploration of the urban landscape, Sheeler created paintings of some of the scenes. He followed his usual technique of taking photographs and drawing sketches before committing the image to paint.

In New York, Sheeler became friends with poet William Carlos Williams. Precision with words was a hallmark of Williams' writing, and it matched Sheeler's attention to structure and forms in his painting and photography. They attended speakeasies together with their wives during the Prohibition years.

Another important friendship developed with the French artist Marcel Duchamp. The pair shared an appreciation of the Dada movement's break from concern about traditional notions of aesthetics.

Sheeler considered his 1929 painting "Upper Deck" a powerful representation of all that he'd learned to that point about art. He based the work on a photograph of the German steamship S.S. Majestic. To Sheeler, it allowed him to use the structures of abstract painting to represent something entirely realistic.

In the 1930s, Sheeler painted celebrated scenes of the Ford Motor Company River Rouge plant based on his own photographs. At first glance, his 1930 painting American Landscape appears peaceful like a traditional pastoral landscape painting. However, all of the subject matter is the result of American technological might. It is an example of what was called the "industrial sublime."

By the 1950s, Sheeler's painting turned toward abstraction as he created works that featured parts of larger structures like his bright-colored "Golden Gate" showing a close-up portion of San Francisco's iconic Golden Gate Bridge.

Charles Sheeler worked for corporate photography clients throughout his career. He joined the staff of the Conde Nast magazine publishing firm in 1926 and worked regularly on articles in Vogue and Vanity Fair until 1931 when he was offered regular gallery representation in Manhattan. In late 1927 and early 1928, Sheeler spent six weeks photographing Ford Motor Company's River Rouge production plant. His images received strong positive acclaim. Among the most memorable was "Crissed Crossed Conveyors."

By the late 1930s, Sheeler was so prominent that Life magazine ran a story on him as their first featured American artist in 1938. The next year New York's Museum of Modern Art conducted the first Charles Sheeler museum retrospective including over one hundred paintings and drawings and seventy-three photographs. William Carlos Williams wrote the exhibition catalog.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Sheeler worked with additional corporations such as General Motors, U.S. Steel, and Kodak. He also worked for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in the 1940s photographing items from their collections. Sheeler cultivated friendships with other renowned photographers including Edward Weston and Ansel Adams.

By his own definition, Charle Sheeler was part of the distinctly American movement in the arts called Precisionism. It is one of the earliest modernist styles. It is most often characterized by a precise depiction of the strong geometric lines and forms found in realistic subject matter. The works of precisionist artists celebrated the new industrial American landscape of skyscrapers, factories, and bridges.

Influenced by Cubism and presaging Pop Art, Precisionism avoided social and political commentary while the artists rendered their image in an exact, almost rigid style. Among the key figures were Charles Demuth, Joseph Stella, and Charles Sheeler himself. Georgia O'Keefe's husband, photographer, and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz was a strong supporter of the movement. By the 1950s, many observers considered the style outdated.

Sheeler's style in his later years remained distinctive. He abstracted subjects into an almost flat plane of lines and angles. In 1959, Charles Sheeler suffered a debilitating stroke which ended his active career. He died in 1965.

Charles Sheeler's focus on industry and cityscapes as subjects for his art influenced the Beat movement of the 1950s. Author Allen Ginsberg, in particular, taught himself photography skills to emulate Sheeler's groundbreaking work. Sheeler's photography blurred the boundaries between commercial and fine art when he eagerly embraced industrial corporations and artistic depictions of their production plants and products.